In what are considered the first anthropological films, the Lumiere brothers captured the daily lives of ordinary individuals in society. In light of the novelty of the technology at this time, however, these films were later criticized as spectacles of self-conscious humanity. The field of anthropology began to lean ever more toward lexical ethnographic data collection and presentation, as the genre of filmmaking diverged toward the technical and imaginative processes of the filmmakers themselves. Today, both the technologies involved in making visual ethnographies as well as the publication of such documentation are readily available to anyone in possession of a camera and a computer. Such a trend begs one to examine the following: In what ways are anthropology and film converging in this era of interactive technologies?

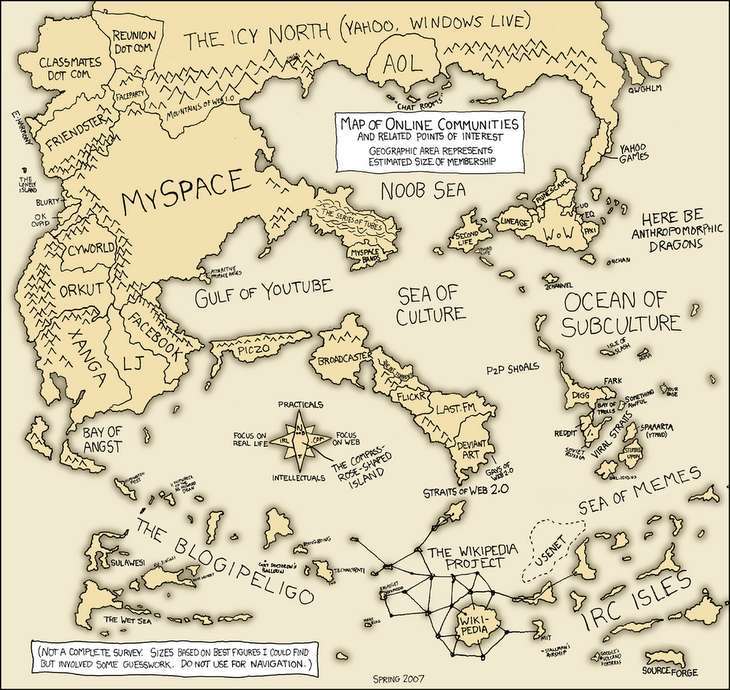

Little more than two years old, YouTube (whose motto is “Broadcast Yourself”.) has fast become one of the most popular sites on the web. Users can create accounts in order to share videos with friends, comment on the videos of others, save favorite clips, and create playlists. Unlike television, YouTube is a fully interactive medium. The service is free of charge, allowing anyone to view videos generated from around the world and engage in discourse with other viewers. The Internet is truly a point of liminality, that space in between ephemeral experience and the social structure- that which is without structure itself but works to create it.

Anthropology as a discipline is dependent upon claims to expertise. However, there has been “an increasing recognition that ethnographic understanding involves a process, and that it is mediated through subjective exchange (Grimshaw 170).” One could find no better way of describing the YouTube community in anthropological terms. What film lacks in depth of lexical discussion, YouTube makes up for in the sheer quantity and variety of subjective understandings available. Its tendency to depict life informally recalls the fundamental nature of ethnography itself, though it is not without a fair share of self-consciousness.

A central tenet of applied anthropology in particular is depicting the issues faced by subordinate peoples. Anna Grimshaw discusses one of the major flaws of anthropology- its specialized, inaccessible nature does little to promote public visibility of issues such as human rights, oppression, and war. The work of Llewelyn-Davies in televising her documentary fieldwork with the Maasai women, informal in nature, seems a proper precedent for the emergence of ethnographic video on the Internet. Drawing on feminist practices of giving voice to the oppressed, the Internet has become a virtual arena for the politically concerned. A quick search of YouTube with the term “Baghdad” yielded 2,490 video clips. Television and Internet mediums share the power of evoking embodied viewing by the audience, who are able to engage with the subjects from the comfort of their own homes.

In light of the current postmodern trend in anthropological thought, a discussion of the reflexive and discursive nature of YouTube is also warranted. These elements are exemplified in a short clip by a Michigan State University student, who asked the question “why do you tube?” His question generated 364 video responses from members of the YouTube community, many of whom described the allure of acquiring insight into the lives of people different from their own, a shining example of globalization in practice. It is this element, as well as YouTube’s capacity to evoke public engagement with ethnographic film, that I seek to explore further in an extended work.

April 3, 2007

Full Circle? From the Lumiere Brothers to YouTube

Labels:

ethnography,

intersubjectivity,

liminality,

visual anthropology,

youtube

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment